Rooted In Experience:

How Farmer-Led Advisory Networks Can Transform Agriculture

Author: Julie Davenson, Director of Program Integration and Financial Services, Soil & Climate Initiative

(Center) Adam Chappell, SCI Regional Technical Advisor & Owner of Chappell Farm

Who holds expertise in agriculture? Traditional agricultural advisory systems in the United States have long been built on a one-way flow of information – from university researchers, extension agents, and industry consultants to farmers. This top-down model overlooks a fundamental truth: farmers themselves are among agriculture’s most valuable sources of knowledge and innovation.

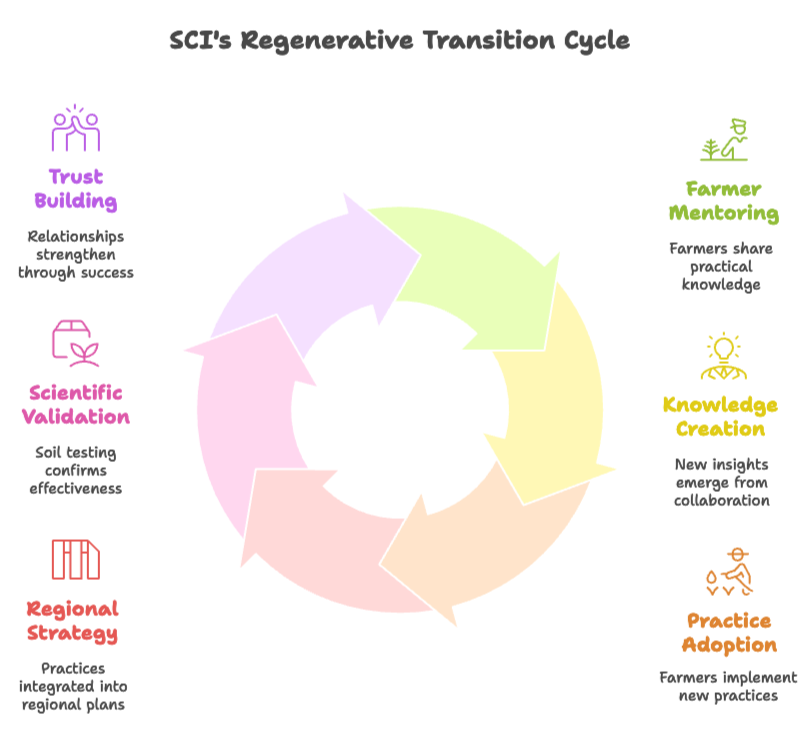

While outside experts provide valuable knowledge, farmer-to-farmer mentoring has proven highly effective in producing knowledge and adapting soil health practices into specific farm and regional contexts. Programs like the Minnesota Soil Health Coalition’s mentor program the Transition to Organic Partnership Program demonstrate this success. Adapting this approach, SCI contracts successful and highly experienced regenerative farmers to provide regional technical assistance and support alongside SCI's popular transition framework and rigorous soil testing services. Centering farmers as experts in SCI’s Regenerative Transition Services (RTS) was a logical evolution with many benefits across the value chain.

In the RTS program, farmers are contracted as technical advisors to support a cohort of SCI enrolled farmers in their region. The technical assistance and mentoring are folded into a broader regional strategy to transition supply chains in three areas of the country; the Upper Midwest, Delta and Great Plains. This model recognizes farmers as creators of sophisticated knowledge with both practical and economic dimensions that build trust. SCI’s network of regional farmer technical advisors including longtime farmer-advisor Russell Hedrick from North Carolina, Adam Chappell from Chappell Farm in Arkansas, Tom Cotter from Cotter Farm in Minnesota, and Micheal Thompson whose farm straddles the borders in the great plains of Kansas and Nebraska. This approach to regenerative transition is wedding scientific knowledge, (via soil testing), with local knowledge within a structured framework so there's replicability, comparability, and a level of rigor to deliver results on the farm. Hope you're all handling this busy season well despite weather and market challenges.

The SCI model represents a meaningful step toward what Lubell et al. (2014) call "Extension 3.0" — a networked approach to agricultural knowledge systems that prioritizes farmer agency and regional context.

This creates a more effective knowledge transfer system that recognizes farmers as creators of valuable, context-specific knowledge who can bridge the gap between scientific research and practical implementation. By compensating farmers for their intellectual contributions and fostering peer-to-peer learning networks, SCI’s farm transition program delivers insights with real agronomic and economic practicality with regional specificity, while building trust-based relationships that enhance adoption rates.

SCI’s approach to delivering technical support reinforces the significant responsibility inherent in guiding agricultural transitions. Cotter expresses, "When farmers trust you with their transition process, they're putting their financial future in your hands. That's a responsibility I take extremely seriously—it's about finding what works for their specific situation, not pushing a particular agenda."

Farmer technical advisors like Cotter understand the risks and are not motivated by external pressures to push practices before farmers are ready. This approach addresses both the ethical and equity concerns that can undermine traditional models of transition programs.

“When farmers trust you with their transition process, they’re putting their financial future in your hands. That’s a responsibility I take extremely seriously—it’s about finding what works for their specific situation, not pushing a particular agenda.”

Learning Modalities in Farmer-to-Farmer Education

The SCI approach is based on social science research. It operates through three distinct, but interconnected learning modalities identified by social learning theorists (Bandura, 1977; Wenger, 1998):

Cognitive Learning

Cognitive learning in agricultural transitions refers to the acquisition, processing, and application of knowledge and understanding needed to successfully implement regenerative practices. This includes technical knowledge, practical skills, problem-solving abilities, and the mental frameworks farmers use to make decisions about their operations.

SCI’s Senior Manager of Farm Transition Services, Taylor Herren, explains the fundamental value this approach delivers: "There's a lot between a high-level recommendations of planting rye and what it means to plant that rye with success... what equipment you're using... seeding rate... so much depends on your soil type, your climate, the weeds — all this stuff that you actually just can't answer unless you've farmed it." This gap between general principles and successful implementation represents years of hard-won experience. "These farmers have been doing it for ten, fifteen, twenty, years. They're trying things, they're messing up...That investment and getting your butt kicked: what a gift to give someone!" Herren observes.

“I think what sets it (farmers as technical advisors) apart is you as a producer can answer the real questions on how to make it work financially... you’ve got to know that the payback is there. You’ve really got to know what works at what rates.”

Michael Thompson, SCI Regional Technical Advisor & Owner of Thompson Farm and Ranch

The knowledge farmers glean through taking risks, and failing, is just as valuable as successes garnered, especially when advising farmers who may not have the margins to absorb risky transitions. Thompson explains: "I think what sets it (farmers as technical advisors) apart is you as a producer can answer the real questions on how to make it work financially... you've got to know that the payback is there. You've really got to know what works at what rates." Thompson’s point illustrates the application of the cognitive learning in terms of the practical economic knowledge and technical understanding of implementation rates and financial viability.

Relational Learning

Relational learning in regenerative agriculture transitions refers to the knowledge and skills acquired through social interactions, peer networks, and trust-based relationships that enable farmers to successfully navigate complex agricultural changes. Drawing from social learning theory (Bandura, 1977) and Communities of Practice frameworks (Wenger, 1998), this learning occurs through relationships rather than formal instruction.

Thompson describes the evolution of relational learning networks: "A lot of these mentorships actually branch out to be like a peer network... they find friendships or find people that they trust. When you get these peer-based networks... it really just spreads a lot of goodwill and it spreads a lot of success, breeds more success.”

Normative Learning

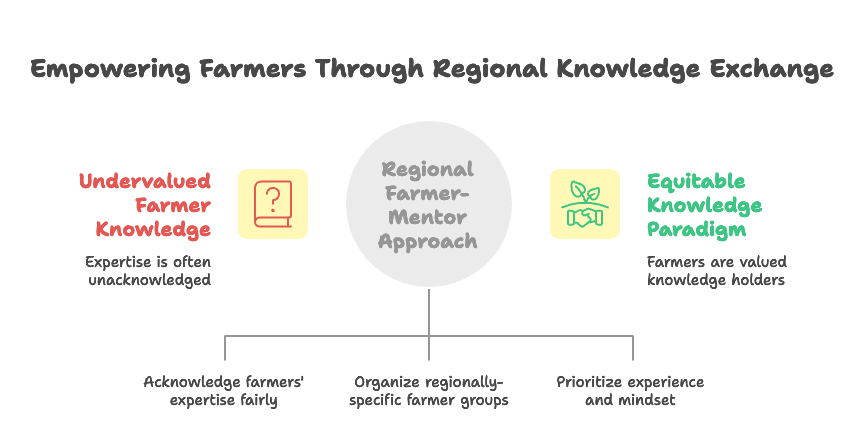

Normative learning addresses values, motivations, and beliefs about what is important or "right" in agricultural transitions. In the case of farmer mentors, it involves shifting values around who holds legitimate knowledge, what farmers deserve, and how agricultural support should operate.

“It’s a lot easier to turn lose the time if you’re compensated for it. Everybody that has a job is getting paid for their time.”

Traditional agricultural support structures have systematically undervalued farmer knowledge while simultaneously expecting farmers to share it freely. When asked about compensation, Chappell is direct: "It's a lot easier to turn lose the time if you're compensated for it. Everybody that has a job is getting paid for their time." Herren, a beginning farmer herself, underscores the level of knowledge and expertise necessary to navigate regenerative agriculture transitions, “Think about someone who gets a ton of education. Those are the type of people that get paid so much money, fancy consultants and lawyers. Being an advanced regenerative farmer is, you know, you are a mechanic and ecologist, a soil scientist."

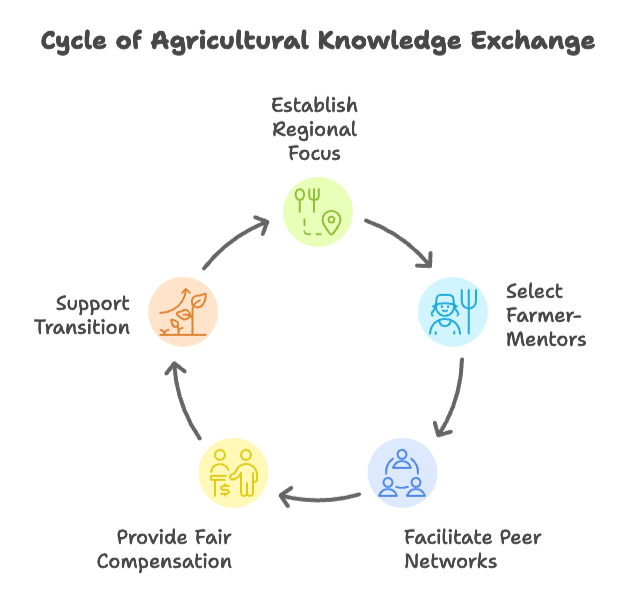

The Regional Cohort Model

The SCI regional cohort model centers on two transformative structural elements: regional cohorts and farmer technical advisors:

Regional Specificity: Organizing cohorts by geography ensures context-appropriate advice

Farmer Technical Advisors: Hiring accomplished regional farmers as paid technical advisors

This approach draws from established theoretical frameworks such as Communities of Practice (Wenger, 1998), which emphasizes learning through shared practice, and Knowledge Co-Production (Jasanoff, 2004), which recognizes the value of integrating multiple forms of expertise.

Farmer Adam Chappell reinforces this perspective from the practitioner's side: "Regional knowledge is the most important thing you can have. I don't know anything about farming in Colorado or anywhere like that. For somebody to say they can go and do this anywhere and be successful in year one is pretty arrogant, honestly, and ignorant also." Research by Warner (2007) on agroecological knowledge networks confirms this insight, demonstrating that context-specific knowledge shared through farmer-to-farmer networks facilitates more successful adoption of sustainable practices than expert-led approaches.

“Regional knowledge is the most important thing you can have. I don’t know anything about farming in Colorado or anywhere like that. For somebody to say they can go and do this anywhere and be successful in year one is pretty arrogant, honestly, and ignorant also.”

This regional focus also allows for appropriate risk assessment. Thompson notes, "Somebody that's in a higher debt load is going to have to take smaller bites. You've got to throttle maybe the ones that are super risk takers back a little bit... And then there's other people that might be cautious and hesitant... they need to have a little bit more of that push." Unlike conventional technical assistance programs focused on selling products or offering detached expertise, the regional farmer-mentor approach ensures a successful transition by embedding support in real-world experience. The mentors have navigated the same challenges, understand the regional context, and share in both the risks and rewards of agricultural innovation. Thompson explains how this approach accelerates success: "It's really important to network with people from your region so that you don't make the same mistakes over and over. Us older people have made a lot of mistakes and learned a lot about what works and what doesn't work and kind of how hard to push the system."

The regional focus also addresses the challenging relationship between markets and transitions. Research by Carlisle (2016) identifies economic constraints as a major barrier to adoption of soil health practices. By working in regional cohorts, SCI can aggregate and connect farmers to market opportunities and buyers on both the regional and national level. Most transition programs end on the farm, with farmers bearing the majority of the risk while companies remain insulated from the consequences. When farmers grow crops without forward contracts, they're vulnerable if companies withdraw purchase commitments—which happens frequently. Companies that truly share in the risk by making firm purchasing commitments throughout and beyond the transition period significantly reduce this pressure. A CPG brand in the Upper Midwest cohort exemplifies this relational approach to contracting and purchasing from farmers incorporating diverse crop rotations, including sunflower seeds. Seven Sundays pays premiums and financially supports regenerative transitions in the region for farmers. An on-ramp period is necessary to support the adoption of practices and risks the sector is asking farms to take. This commitment reframes transition support as an essential investment rather than an optional charity.

Selecting the Right Mentors

SCI’s mentor selection process prioritizes both technical credibility and the appropriate mindset to support other farmers through difficult transitions. Herren's criteria to select mentors included farmers who were actively farming rather than consulting for a living, able to demonstrate the economic viability of soil health practices through positive cash flows in their businesses, engaged in their local agricultural communities (all are involved in leadership positions in their local agricultural communities), and possessing an adaptive mindset with an inclusive perspective that avoids judgment about different farming approaches.

As Cotter explains, "The best advisors are the ones still figuring things out on their own land every day. We understand what it means to make these decisions when your family's livelihood depends on getting it right."

“The best advisors are the ones still figuring things out on their own land every day. We understand what it means to make these decisions when your family’s livelihood depends on getting it right.”

Tom Cotter, SCI Regional Technical Advisor & Owner of Cotter Farms

Herren describes the criteria she used to select farmers mentors who “have purposely not built a business as consultants. Their perspectives are nonjudgmental and agnostic around organic or not chemical and are willing to have a lot of empathy. All three of these farmers have farms that positively cash flow."

From Mentorship to Network

Research consistently demonstrates that peer-to-peer learning produces higher adoption rates and more sustainable outcomes (Warner, 2007; Kroma, 2006). By compensating farmer-mentors fairly, organizing regionally-specific cohorts, and creating conditions for ongoing relationship building, this model addresses the social, economic, and ecological dimensions of agricultural transition simultaneously.

“You can’t really talk to your neighbor, because if your neighbor’s not doing the same thing or understanding your context, they’re going to just say, ‘Oh, that’s crazy, that’ll never work. Whereas they’re (transitioning farmers) looking for people that are kind of doing these things throughout your region.”

The SCI program also offers valuable opportunities for farmers to find and connect with each other through peer-to-peer networking in monthly meetings. A remarkable transformation occurs when mentorship evolves into peer networks. These enduring relationships create value beyond the formal program. Thompson expresses the challenges farmers on the leading edge of innovation face in finding support. "You can't really talk to your neighbor, because if your neighbor's not doing the same thing or understanding your context, they're going to just say, 'Oh, that's crazy, that'll never work,'" Thompson explains. "Whereas they're (transitioning farmers) looking for people that are kind of doing these things throughout your region."

Fair Compensation for Knowledge

SCI's approach exemplifies what Ingram (2008) identified as effective knowledge exchange: treating farmers as equal partners in knowledge production. SCI's mentor approach recognizes both the effectiveness and equity dimensions of agricultural knowledge. By compensating farmers for their intellectual contributions, the program acknowledges that valuable expertise deserves fair payment.

Traditional agricultural support structures have systematically undervalued farmer knowledge while expecting farmers to share it freely. Chappell describes how this extractive relationship plays out: "I felt like they (external consultants) were out of their depths down here and they were using me to try to figure out how to do what, and I didn't appreciate that at all." When asked about compensation, Chappell is direct, “I've done a lot of this stuff for free and if you do something for free and people hear about it, you're going to be doing a lot of it for free."

“Being paid for my knowledge allows me to prioritize this work properly. It’s not just an afterthought I squeeze in between farm tasks—it becomes a legitimate part of my professional contributions to agriculture.”

Cotter describes the multifaceted dimension of knowledge required: "When you're implementing these practices, you need to understand your soils, your climate, your equipment, and your markets all at once. That's specialized knowledge that deserves recognition." Cotter highlights how compensation changes the relationship: "Being paid for my knowledge allows me to prioritize this work properly. It's not just an afterthought I squeeze in between farm tasks—it becomes a legitimate part of my professional contributions to agriculture." This perspective aligns with research on knowledge justice in agricultural transitions (Bezner Kerr et al., 2019), which highlights how power dynamics in knowledge validation often disadvantage farmers.

Toward a New Agricultural Knowledge Paradigm

By centering farmers as knowledge holders and compensating them appropriately, SCI is addressing both effectiveness and equity concerns. As Herren notes, this work carries ethical responsibilities: " We've got an obligation to set proper expectations and have good boundaries. (Transition should) not be a place where we are leading people down a path 'cause they are coming to us out of desperation. What a privilege to really help someone achieve what Adam's doing here. It's the greatest gift that we could give. But we have to be super humble about it and clear-eyed about it."

“We’ve (SCI) got an obligation to set proper expectations and have good boundaries. (Transition should) not be a place where we are leading people down a path ‘cause they are coming to us out of desperation.”

(Left) Taylor Herren, SCI Senior Manager, Farm Transition Services (Right) Russell Hedrick, SCI Regional Technical Advisor and Co-Founder of Soil Regen

The farmer-to-farmer framework combines cognitive, relational, and normative learning to create outcomes that benefit farmers ecologically, economically, and socially while addressing longstanding inequities in how agricultural knowledge is valued and shared. This approach doesn't merely transfer knowledge — it co-creates it through relationships grounded in shared experience, mutual respect, and fair compensation. This approach shifts how agricultural knowledge is valued, created, and shared. By centering farmers as the authorities on practical implementation in their regions, SCI is building a more effective and equitable approach to agricultural transition, one that respects the sophisticated expertise that can only come from years on the land.

If we genuinely want to support regenerative farm transitions at scale, investing in regional and farmer-led models offers the highest return on investment—creating resilience for individual farmers, rebuilding community knowledge networks, restoring environmental health, and ultimately securing greater stability in our food supply. This approach recognizes that the most valuable agricultural knowledge doesn't just exist in research papers or corporate offices, but in the lived experience of farmers who have successfully navigated these transitions themselves.

This approach recognizes that the most valuable agricultural knowledge doesn't just exist in research papers or corporate offices, but in the lived experience of farmers who have successfully navigated these transitions themselves.

About the Author

Julie Davenson

Director of Program Integration and Financial Services, Soil & Climate Initiative

Julie Davenson brings diverse experience to the SCI ranging from managing organic and regenerative farms, policy and running a regenerative livestock processing and distribution company in the northeast. She is also fellow with the Gund Institute for the Environment and Institute for Agroecology at the University of Vermont researching ecological economics and transformative food system governance.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Prentice-Hall.

Bezner Kerr, R., et al. (2019). Repairing rifts or reproducing inequalities? Agroecology, food sovereignty, and gender justice in Malawi. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 46(7), 1499-1518.

Carlisle, L. (2016). Factors influencing farmer adoption of soil health practices in the United States: a narrative review. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 40(6), 583-613.

Dolinska, A., & d'Aquino, P. (2016). Farmers as agents in innovation systems. Empowering farmers for innovation through communities of practice. Agricultural Systems, 142, 122-130.

Ingram, J. (2008). Agronomist–farmer knowledge encounters: an analysis of knowledge exchange in the context of best management practices in England. Agriculture and Human Values, 25(3), 405-418.

Jasanoff, S. (2004). States of Knowledge: The Co-Production of Science and Social Order. Routledge.

Kroma, M. M. (2006). Organic Farmer Networks: Facilitating Learning and Innovation for Sustainable Agriculture. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 28(4), 5-28.

Lubell, M., Niles, M., & Hoffman, M. (2014). Extension 3.0: Managing Agricultural Knowledge Systems in the Network Age. Society & Natural Resources, 27(10), 1089-1103.

Šūmane, S., et al. (2018). Local and farmers' knowledge matters! How integrating informal and formal knowledge enhances sustainable and resilient agriculture. Journal of Rural Studies, 59, 232-241.

Warner, K. D. (2007). Agroecology in Action: Extending Alternative Agriculture through Social Networks. MIT Press.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge University Press.